My Encounter With Mongolian Yak-Hunters.

On

October 5th ,1896 we set off from the small village of Koko-bureh on

October 5th 1896 after a few days of much needed and well-earned

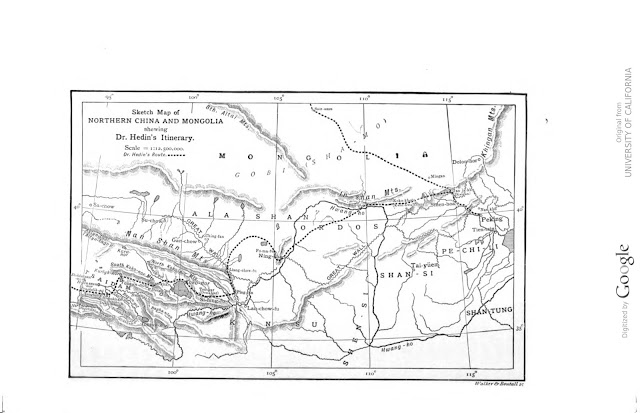

rest. We had departed from Dalai-kurgan in Northern Tibet two months prior with

the intention of reaching the Chinese capital of Beijing via Southern Mongolia.

We made our way down into the Yikeh-Tsohan-Gol valley ridding atop traditional

Mongolian horses. A problem quickly arose as the horses that we travelled upon

were unshod and our path took us along side the bank of a local stream

containing a great deal of sharp angular rocks that wrecked havoc upon their

defenceless feet. But alas we had to press on and continue on our journey if we

hoped to reach a suitable campsite before dark. As we progressed further into

the valley we stumbled across a party of mounted Mongols armed to teeth with an

assortment of primitive weaponry (muskets and traditional Mongolian knives) traveling

in the opposite direction. My men quickly reached for their rifles and it

seemed as if a stand off was inevitable! However, with the assistance of my newly hired

Mongolian interpreter Dorcheh I was able to quickly defuse the situation and

not only that, but I was able to successfully convince them to accompany us to

a suitable location to establish a campsite for the evening.

We

carried on as a group until we arrived in the district of Harato after having only covered a distance of 9 and ¼

miles. We made camp at an altitude of

11,060 feet. As the men busied them

selves setting up camp I decided to use this time to get to know my new travel

companions. The group consisted of 5 Mongol men and one Mongol woman who were

on their way from Yikeh-tsohan-gol to Mosoto where they planned to head higher

in to the mountains to procure a readily available supply of Yak beef for the

winter. These Mongols had planed for an expedition of 15-20 days but only

carried with them provisions and supplies for 5 to 6 days. The plan was that

once theses provisions had been depleted they shall turn to the hunting of

Yaks. Once they had hunted enough Yak

meat to make it through the winter they then planned to load the meat onto

their horses and make the return journey on foot.

I

quickly learned that I had entered Mongolia during the height of the Yak

hunting season. The time of the year when the Yaks make the migration from the

Peripheral regions in the quest for better herbage. The Mongolians hunt in a

rather peculiar fashion. A minimum of two men, sometimes more will confront a

single yak so that in the event the injured beast turns upon a single hunter

the other will be well positioned to put a stop to any attempt. These Yak hunters were quite an extraordinary

people, extremely cheerful and in good humour. I was extremely surprised. Never

in all my travels have I encountered such a joyful and content people who

possessed so little! Perhaps this is due the fact that the Yak hunting seasons

represents a break from their other wise monotonous nomadic form of life.

The

Yak-hunting season lasts for a duration of approximately one month each

October. Each hunting group lays claim to there own well recognized ancestrally

inherited hunting grounds with clearly laid out and defined limitations and

boundaries. What is perhaps most

incredible of this situation is that the hunters spent the entirety of the

duration of this month living in the open air, with not even a tent for shelter.

The only encumbrance these people carry are the clothes they wear, their

saddles, their muskets and small supply of provisions carried in leathern

knapsacks.

These

Mongols quickly made camp within the large pile of bushes located adjacent to

my tent. They immediately set to work constructing a large fire situated

between 3 stones between which they hung a large cooking pot filled with water.

As I approached the group is was immediately greeted with a friendly “Amir

san?” which is Mongolian speak for “How are are you getting on?”.

When

the water began to one boil one of the older men produced 6 wooden bowls from

his back pack and immediately proceeded to distribute them among the remaining

members of the party. Each person was given a portion of parley-meal which had

been enriched with a few slices of a sausage made from mutton lard. Following

this a ladle full of boiling water was added and the Mongolians eagerly dug

into this messy, sorry excuse for a meal. My trusty translator Dorcheh informed

me that this meal was known as tsamba and that it represented the traditional

national dish of the Mongolians. After the Mongolians had eagerly consumed this

minuscule meal they produced their pipes and quickly filled them with what is perhaps

the most vile form of Chinese tobacco I have even seen and began to puff away

in a state of great content.

I

used this time to examine and note the rest of the Mongols provisions. There

clothing seemed to consist of a sheep skin pelt worn close to the skin followed

by a par of breeches, boots and caps. These Mongols seemed quite impervious to

the cold as their right arms and in fact the whole right side of there body

from the waist up was left bare and open to elements. During the night they

merely wrapped themselves in their pelts and crept close to the fire and laid

down upon there saddles and saddle rugs while keeping their muskets within arms

reach. They wore their hair in plaits and busied them selves reciting an odd

prayer “On Menh padmeh hum” the meaning of which escapes me to this very day!

The

following morning the Mongol’s sold us a few of their horses and eagerly

departed for their hunting grounds but not before informing me and Dorcheh of a

near by settlement located but a day’s ride from our current location. It

wasn’t long before that we realized that we had been duped in this transaction

and at the first chance the horses tried to escape in the general direction of

their previous owners. I immediately dispatched two men upon horse back to

retrieve the wayward animals. Me and

Dorcheh continued a head along the stream bank until night fall in the hope of

reaching the Mongolian settlement before night fall. It wasn’t long before we

began to see the lights of numerous fires off in the distance. Could this be my

first encounter with a true Mongolian encampment? Dorchech sent me along ahead

with the promise that he would return shortly with the 2 men and the way ward

horses.

As

I approached the Mongol camp I was greeted by a swarm of Mongolian dogs who immediately

raised the alarm. I quickly fastened my horse out side of a near by tent and

immediately entered. There were half a dozen Mongols seated in circle around a fire.

They looked up at me in amazement. I greeted them a customary “Amir San?” and

sat down beside them and light up my pipe. I saw a pan containing what I now

know to be fermented mares milk in the near by corner and promptly helped my

self. It tasted rather peculiar quite like a small beer. The Mongols continued

to stare at me not uttering a single word for nearly two hours when Dorcheh

finally arrived with the rest of our caravan and explained our current

situation. A fire was quickly made in an

open space situation within a gap in the Mongolian tents and my tent was

pitched nearby. I learnt that the named

of this community was known as Yikeh-tsohan-gol and I made the decision to

settle down for a few more days in order to acquire urgently needed fresh horses

and saddles which the local Mongolians quickly produced with great swiftness

and eagerness.

Source

Hedin, Sven Anders, and J. T. Bealby. 1899. Through Asia. New York and London: Harper and Bros. This book is Sven Hedin’s first-hand account of what is known as his first large expedition throughout Central Asia. The chapter used for this entry is chapter LXXXVIII “Among The Mongols of Tsaidam”.

Comments

Post a Comment